With his refusal to race on Sunday, the Scottish sprinter showcased a bigger story about Christians in sports.

Written by Paul Emory Putz - July 1, 2024

Eric Liddell took his starting spot in the finals for the 400 meters. More than 6,000 paying spectators filled the stadium on that warm Friday night in Paris, a century ago, when the starting pistol fired and the Scottish runner took off from the outside lane.

And 47.6 seconds later, Liddell had set a new world record, leaving his competitors in awe and his fans grasping to make sense of what they had just witnessed.

Liddell’s sprint at the 1924 Paris Olympics is a canon event in the history of Christian athletes, and not just because of what happened on the track. Liddell entered the 400-meter race only after learning that the heats for his best Olympic event, the 100 meters, would fall on a Sunday. He withdrew from that event, holding fast to his Christian convictions about observing the Sabbath.

Sports matter to us in large part because of the cultural narratives that give them significance. It’s not just that athletes run, jump, reach, and throw with remarkable skill. It’s that those bodily movements are fashioned and framed into broader webs of meaning that help us make sense of the world around us—both what is and what ought to be.

Liddell’s performance in 1924 lingers because it was caught up in cultural narratives about what it means to be a Christian athlete and, by extension, what it means to be a Christian in a changing world.

His story inspired the 1982 Oscar-winning movie Chariots of Fire, which brought his accomplishments back into the spotlight and led to numerous inspirational biographies focused on his Christian legacy.

And as the Olympics return to Paris this summer, Liddell’s name is part of the centennial commemorations. Ministries in Scotland and France are putting on events. The stadium where he raced has been renovated for use in the 2024 games and displays a plaque in his honor. His story still has something to teach us, whether we’re Christian athletes or watching from the stands.

The son of missionaries, Liddell was born in China but spent most of his childhood at a boarding school in London. He was shaped by a broad British evangelicalism, developing habits of prayer, Bible reading, and other practices of the faith. He also had a knack for sports, both rugby and track. Speed was his primary weapon. Standing just 5 feet 9 inches and weighing 155 pounds, his slim frame disguised his strength.

Although he had an unorthodox running style—one competitor said, “He runs almost leaning back, and his chin is almost pointing to heaven”—it did not stop him from emerging as one of Great Britain’s best sprinters. By 1921, as a first-year college student, he was recognized as a potential Olympic contender in the 100 meters.

Although he was a Christian and an athlete, he preferred not to emphasize these combined identities in a public way. He went quietly about his life: studying for school, participating in church, and playing sports.

Things changed in April 1923 when 21-year-old Liddell received a knock on his door from D. P. Thomson, an enterprising young evangelist. Thomson asked Liddell if he would speak at an upcoming event for the Glasgow Students Evangelical Union.

Thomson had toiled for months trying to draw men to his evangelistic events, with little success. As sports writer Duncan Hamilton documented, Thomson reasoned that getting a rugby standout like Liddell might attract the men. So he made the ask.

Later in life, Liddell described the moment he said yes to Thomson’s invitation as the “bravest thing” he had ever done. He was not a dynamic speaker. He did not feel qualified. Stepping out in faith called something out of him. It made him feel as if he had a part to play in God’s story, a responsibility to represent his faith in public life. “Since then the consciousness of being an active member of the Kingdom of Heaven has been very real,” he wrote.

The decision carried with it potential dangers too—particularly, Liddell himself would recognize, the danger of “bringing a man up to a level above the strength of his character.” Success in sports did not necessarily mean that an athlete had a mature faith worthy of emulation. Yet sharing his faith brought greater meaning and significance to Liddell’s athletic efforts, helping him integrate his identities as a Christian and an athlete.

Liddell’s decision to speak up in April 1923 set the stage for his decision later that year to step down from Olympic consideration in the 100 meters. He communicated his intentions privately and behind the scenes, with no public fanfare. It became newsworthy, as Hamilton recounts in his biography of Liddell, only when the press became aware and began sharing their opinions.

Some admired his convictions, while others saw him as disloyal and unpatriotic. Many could not comprehend his inflexible stand. It was just one Sunday, and at a time when Sabbath practices in the English-speaking world were rapidly changing. Besides, the event itself would not happen until the afternoon, giving Liddell plenty of time to attend church services in the morning. Why give up a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to bring honor to himself and his country?

Liddell recognized that the world was changing. But the Sabbath, as he understood and practiced it, was to be a full day of worship and rest. It was, for him, a matter of personal integrity and Christian obedience.

And he was not alone in his convictions. In the United States into the 1960s, many evangelicals continued to see full Sabbath observance as a central part of Christian witness. To compete on Sunday was a sign that one might not be a Christian at all—an indicator, one evangelical leader suggested, “that we are either ‘dead in trespasses and sins’ or sadly backslidden and desperately in need of revival.”

Throughout the public debate about his decision, Liddell did not raise complaints about discrimination and oppression. He did not blast the Olympic committee for their refusal to accommodate Sabbath-keeping Christians. He did not take aim at fellow Christian athletes for their willingness to compromise and compete on Sunday. He simply made his decision and accepted the consequences: Gold in the 100 meters was not an option.

If this were the end of the story, Liddell’s example would be an inspiring model of faithfulness—and also a forgotten footnote in history. There is no Chariots of Fire without his triumph in the 400 meters.

Few expected him to have a chance in the significantly longer race. Still, he did not arrive in Paris unprepared. He had a supportive trainer who was willing to adapt, working with Liddell for several months to build him up for both of his Olympic events (Liddell also won bronze in the 200 meters).

He also inadvertently had the science of running on his side. As John W. Keddie, another Liddell biographer, has explained, many then believed that the 400 meters required runners to pace themselves for the final stretch. Liddell took a different approach. Instead of holding back for the end, Keddie said, Liddell used his speed to push the boundaries of what was possible, turning the race into a start-to-finish sprint.

Liddell later described his approach as “running the first 200 meters as hard as I could, and then, with God’s help, running the second 200 meters even harder.” Horatio Fitch, the runner who came in second, saw things in a similar light. “I couldn’t believe a man could set such a pace and finish,” he said.

Beyond the tactics Liddell deployed was a trait that truly great athletes possess: He delivered his best performance when it mattered the most. Running free, without fear of failure, he rose to the occasion in a remarkable way, surprising fans, observers, and fellow competitors. “After Liddell’s race everything else is trivial,” marveled one journalist.

News of Liddell’s achievement quickly spread back home through the press and the radio. He arrived in Scotland as a conquering hero; those who had criticized his Sabbath convictions now praised him for his principled stand.

Biographer Russell W. Ramsey described how he spent the next year traveling with Thomson throughout Great Britain on an evangelistic campaign, preaching a simple and direct message. “In Jesus Christ you will find a leader worthy of all your devotion and mine,” he told the crowds.

Then, in 1925, he departed for China, spending the rest of his life in missionary service before dying in 1945 of a brain tumor at age 43.

In the decades after Liddell’s death, Thomson published books about his protégé and friend, ensuring Liddell’s story remained in circulation among British evangelicals. Track and field enthusiasts in Scotland continued to recount his 1924 triumph as a source of national pride, with faith a key part of his identity. Conservative Christians in the United States spoke of Liddell too, as an example of an athlete who maintained his Christian witness while pursuing athletic excellence.

These groups kept the flame burning until 1981, when Chariots of Fire came out, bringing Liddell’s fame to greater heights—and turning him into an icon for a new generation of Christian athletes navigating their place in the modern world of sports.

Of course, some of the tensions Liddell grappled with in 1924 have grown more challenging in our own day—and new ones have been added. The issue of Sunday sports, on which Liddell took his principled stand, seems like a relic of a bygone era. The question these days is not whether elite Christian athletes should play sports on a select few Sundays; it’s whether ordinary Christian families should skip church multiple weekends of the year so their children can chase travel-team glory.

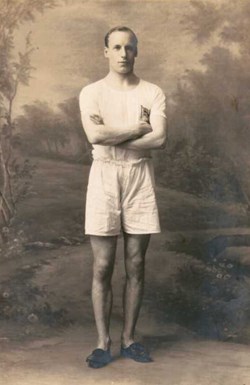

Eric Liddell is paraded around the University of Edinburgh after his Olympics victory.

In this environment, Liddell’s story is not always a direct analog to current situations. It can also leave us with more questions than answers: Is the tendency to turn to celebrity athletes as leading voices for the Christian faith healthy for the church? How successful was Liddell’s witness, really, if his stand for the Sabbath seemed to have no effect on long-term trends? Does Liddell’s example suggest that faith in Christ can enhance one’s athletic performance and lead to success in life? If so, how do we make sense of Liddell’s death at such a young age?

The beauty of Liddell’s remarkable Olympic performance is not that it answers those questions in a precise way. Instead, it reaches us at the level of imagination, inviting us to delight in the possibility of surprise and to consider what is within reach if we prepare ourselves well for the opportunities that come our way.

It gives us Liddell as both the martyr willing to sacrifice athletic glory for his convictions and the winner showing that Christian faith is compatible with athletic success. It presents us with Liddell as the evangelist using sports as a tool for a greater purpose and as the joyful athlete engaging in sports simply for the love of it—and because through it he felt God’s presence.

As we watch the Olympics this year, those multiple meanings—and new ones besides—will be on display as Christian athletes from all over the world take their shot in Paris. Some will know of the famous Scottish runner, and some will not.

But to the extent that they consciously and intentionally strive after Jesus in the midst of their sports—to the extent that they seek to find the meaning of their experience bound up within the bigger story of God’s work in the world—they’ll be following in Liddell’s footsteps.

And maybe they’ll run a race or make a throw or respond to failure in a way that evokes surprise and wonder—and a way that takes its place in a broader narrative about being a faithful Christian in a 21st-century world.

Paul Emory Putz is director of the Faith & Sports Institute at Baylor University’s Truett Seminary.